Estimation: Making realistic estimates

Estimates for completion and delivery of software components or entire projects tend to fail generally. Estimates are continually revised and refined over time, infinitely extending the completion date until it is done. Why is this and what can be done about it?

The talk on estimation by Robert Martin and chapters 2 and 8 of The Mythical Man-Month provides good insight, direction and tactics for improving estimates. These resources along with my own personal experiences at work has helped me formalise my own approach for estimation.

What are we estimating?

This may seem obvious at first, but is not straight forward. Estimates for completion of a software component is generally treated as only the length of time it takes for the actual software development to complete. This is only a small part of the bigger picture. It is important to think about what an estimate should actually involve.

The criteria for estimates should involve:

- Analysis (gathering requirements)

- Designing (architecture, prototyping)

- Developing

- Testing (test suites, QA, UAT, bug fixing, amendments)

- Promoting to Production (attain sign offs, internal admin requirements, red tape)

You may also need to consider documentation or training aswell in your estimates depending on your software or company policy.

If you are making estimates for a larger project (i.e. several software components) then the same criteria for estimates should be applied for all components. The sum of the estimates for each component indicates the work days (also known as man-weeks, man-months) it will take for completion.

Know your resources

By resources I mean people. If you are delegating particular software components to other team members, you should factor in their skills, aptitude and capabilities when estimating how long each part of the criterias above will take for them. Knowing them better will help make a better estimate, as the estimate is tailored for them, than just what you expect from them. Of course you should consult your team members to provide you estimates aswell, but it should encompass the criterias as part of it.

Most importantly, this applies to you. You need to know yourself. The better you know your own abilities, the better your personal estimate will be.

Time and resources are not proportional

A common illusion is to assume that the time to complete a project can be perfectly divisible by the number of people working on it i.e. Time is directly proportional to resources. This is not true.

For example if we have 12 man months of work to complete, the assumption is that if there are 2 people it would take 6 months, with 3 people 4 months, with 4 people 3 months etc… The misconception here is that each person has an output efficiency rate of 100%. This assumes each person has perfect knowlegde of the domain; perfect knowledge of the skillset required; has only independent work and nothing overlapping with the other resources; does not require assistance, collaboration or consultation with other resources; there are no learning curves therefore anyone can join having immediate and full impact. This is obviously theoretical and not realistic at all.

However many resources we have, we must estbalish the overall effective resource rate.

Having 3 resources does not mean our effective resource rate is 3.0, it would be less.

For example the effective resource rate could be 2.0, whereby each resurce utilizes 0.33 of their time for collaborating and consulting with each other or learning the required skills and the domain. Everyone’s individual resource rate would then be 0.67, multiplied by 3 resources would result in the effective resource rate of 2.0.

Therefore 12 man months of work with 3 people working at an effective resource rate of 2.0 would result in a completion time of 6 months.

When establishing the effective resource rate, you will need to consider the environmental and circumstantial factors mentioned above which are natural deviations for any resource from achiving full output efficiency.

The overall effective resource rate is also not proportional to the number of resources. There is a peak effective resource rate value, which essentially represents the optimum number of resources. Adding more resources will cause the effective resource rate value to decrease leading to dimishing returns and making the completion time longer. Infinite resources do not infinitely improve the effective resource rate. You should establish what the optimum effective resource rate would be and therefore know what the optimum number of resources would be to achieve that rate.

Add delays into your estimate

Estimates usually focus on delivering under the assumption of perfect conditions. Rarely does the environment or circumstances we work under allow for forecasts to turn out as estimated. Things go wrong or our attention can get diverted onto other spontaneous tasks or issues outside of the project we are working on, which were not obvious to begin with. These interferences ultimately nullify your orignal estimate requiring you to refine and revise it.

Most initial estimates turn out to be theoretical minimums for completion. How can we predict the unknown and factor this into our estimates?

Defining the ‘unknown’ is the first step, which is what the delay is. I have 3 categories for this: Contingency, Distraction and Absence.

Contingency is additional time due to unforseen implementation complexities or external dependencies that slow down the progress of the project. This is time that is spent while working on the project itself.

Distraction is additional time due to changing priorities that interfere with working on the project. Things such as production issues or spontaneous requirements that divert attention and prohbit progress of the project. This is time that is not spent working on the project which is a time loss.

Absence is additional time due to holidays (public and annual leave entitlement) and other types of non presence (for example sick leave). This is time that is not spent working on the project which is a time loss.

As most estimates are theoretical minimums they do not cater for any of these 3 categories. It assumes all tasks are well defined, with no interference and everyone works without any absences. This is obviously not the reality and is overlooked often.

How much time should be assigned to these categories?

A time range of minimum to maximum should be defined for each category. The values of these should be decided by your intuition and experience. Some are straight forward as for example public holdays can be calculated and annual leave ranges are determiend by your company’s policy.

Are all these categories necessary?

The bigger the project, the longer the project and the more resources involved then the more relevant and necessary these categories are. You may not need all of them if the project is relatively small in delivery, timeline and resourcing.

How can all these categories be combined to determine the delay time?

I have devised formulas for this.

The table below clarifies the components of the formulas:

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| PH | Public Holiday |

| ALm | Minimum Annual Leave |

| ALmx | Maximum Annual Leave |

| Cm | Minimum Contingency |

| Cmx | Maximum Contingency |

| Dm | Minimum Distraction |

| Dmx | Maximum Distraction |

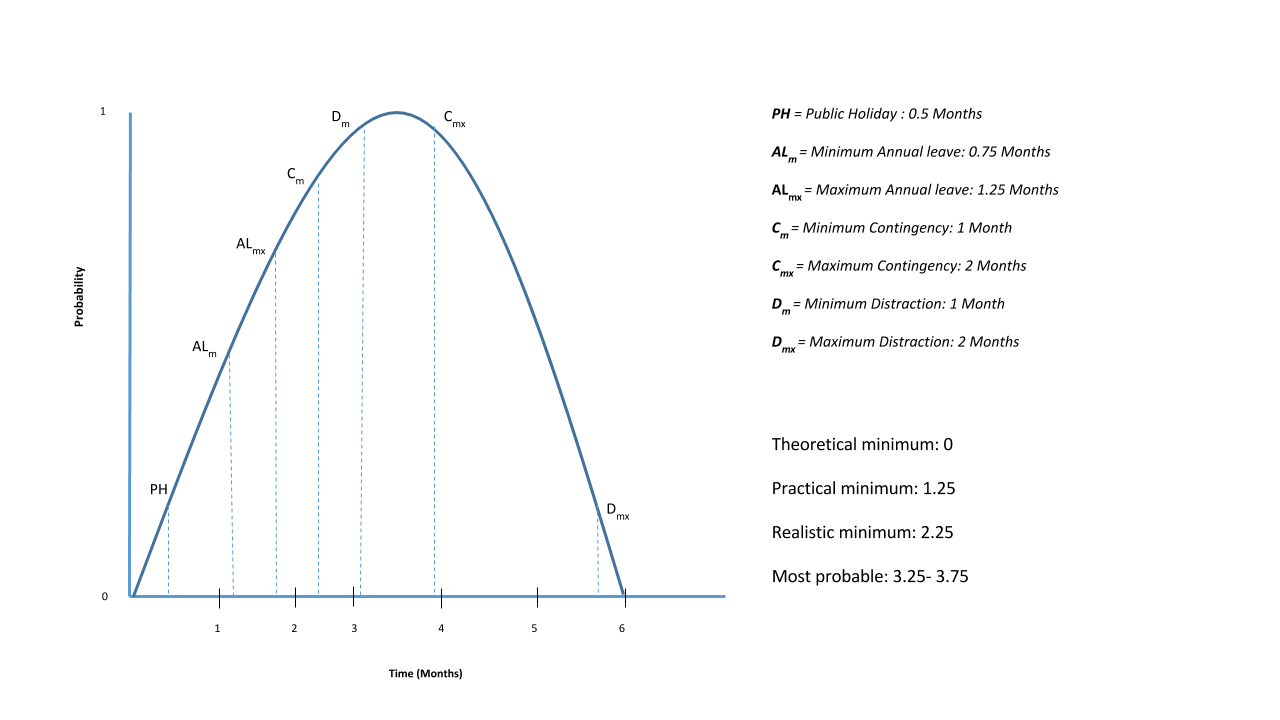

Assuming we have defined an estimate for completion of a project, we can label this as the Theoretical Minimum. The first formula is to establish what the Practical Minimum is by adding onto the Theoretical Minimum:

Practical Minimum = Theoretical Minimum + PH + ALm

Adding public holidays and minimum annual leave is essential as resources will not be working on these days. The amount to include will depend on the timeframe for your project. You can calculate the number of public holidays in this time span and verify the minimum time all your resources will be absent for. It is unlikely for any project to finish before this point, hence the term practical.

The next formula is adding onto the Practical Minimum to establish the Realistic Minimum:

Realistic Minimum = Practical Minimum + Cm

Most projects need contingency time. Adding the minimum contingency time onto public holidays and minimum annual leave provides the first actual target for completion, which is why it is the realistic minimum time for completion.

The next formula is adding onto the Realistic Minimum to establish the Most Probable Minimum:

Most Probable Minimum = Realistic Minimum + Dm

This is optional. If your resources do not have multiple responsibilities and can dedicate their entire time onto the project then there will be no distractions, hence Dm will be 0. Otherwise this value should be added, resulting in the consideration of all minimum category values, which is when the most probable time for completion starts.

The most probable time for completion ends at the Most Probable Maximum:

Most Probable Maximum = Theoretical Minimum + PH + ALmx + Cmx

All projects should end by their maximum contingency time. The upper boundary of this is including maximum annual leave aswell as resources may potentially use up all their entitlement in the project period.

The assumption I have made is that Dm is less than Cmx, which is where the margin in between both is virtually the range between the Most Probable Minimum and Most Probable Maximum (after subtracting the difference between ALmx and ALm).

You can assign numbers to each component and put them into the relevant formulas to calculate each of them. I demonstrate this with an example below.

Example

| Component | Value (Months) |

|---|---|

| Theoretical Minimum | 0 |

| PH | 0.5 |

| ALm | 0.75 |

| ALmx | 1.25 |

| Cm | 1.0 |

| Cmx | 2.0 |

| Dm | 1.0 |

| Dmx | 2.0 |

Practical Minimum = Theoretical Minimum + PH + ALm = 0 + 0.5 + 0.75 = 1.25

Realistic Minimum = Practical Minimum + Cm = 1.25 + 1.0 = 2.25

Most Probable Minimum = Realistic Minimum + Dm = 2.25 + 1.0 = 3.25

Most Probable Maximum = Theoretical Minimum + PH + ALmx + Cmx = 0 + 0.5 + 1.25 + 2 = 3.75Based on all the numbers put into the formulas, the most probable time the project will finish is between 3.25 to 3.75 months after the theoretical minimum.

Conclusion

Making realistic estimates must consider several criterias for the work involved, understand resourcing and incorporate delays. All of this should be formalised and calculated to achieve estimates that are informative, accurate and precise.